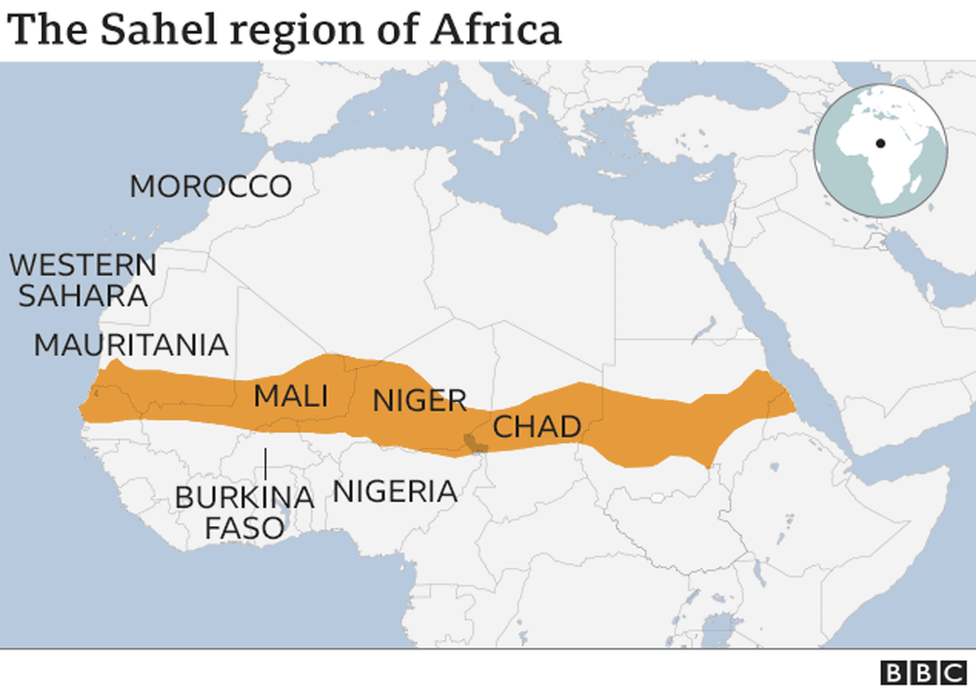

From Mali in the west to Sudan in the east, a whole swathe of Africa is now run by the military.

Niger was one of the few democracies left in the Sahel belt which stretches across the continent. But now that the army has seized power, there are concerns over what this means for the troubled region.

Niger’s President Mohamed Bazoum – a key Western ally in the fight against Islamist militants – was defiant after soldiers announced a coup on Wednesday.

But he has been detained, the army chief has backed military rule, and it isn’t clear who is really in charge.

Former colonial power France and the US have military bases in the uranium-rich country, and both were quick to condemn the coup.

There are concerns that Niger’s new leadership could move away from its Western allies and closer to Russia.

If it does, it would follow the path of two of its neighbours – Burkina Faso and Mali – which have both pivoted towards Moscow since recent military coups of their own.

They had been under intense pressure from Islamist groups which operated freely across much of both countries.

But although Niger had been battling its own jihadist insurgency and rural banditry, it had appeared relatively more stable than its neighbours.

The number of reported deaths from political violence since 2021 was far lower in Niger, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (Acled).

But the jihadist threat was the major reason why the military seized power, arguing that they need to fight against the insurgencies.

Col Maj Amadou Abdramane, who spoke on behalf of the junta, cited the “deterioration of the security situation” and poor socio-economic situation as the reasons for the takeover.

His statement could easily have been made by the coup leaders in either of Niger’s neighbours, despite the very different situation on the ground.

But despite the coups in both those countries, and the presence of a reported 1,000 heavily armed mercenaries from Russia’s Wagner group in Mali, deaths from jihadist attacks have actually risen since the military takeovers.

There have also been well-documented cases of human rights abuses, including the killing of hundreds of civilians in Mali by the security forces and foreign fighters.

President Mohamed Bazoum’s government has also been a partner to European countries trying to stop the flow of migrants across the Mediterranean Sea, agreeing to take back hundreds of migrants from detention centres in Libya.

He has also cracked down on human traffickers in what had been a key transit point between other countries in West Africa and those further north.

That may now be called into question.

And if Western and UN troops are asked to leave Niger – as they have been in Mali and Burkina Faso – it would be a big blow to the fight against Islamic insurgents, who are likely to move quickly to take advantage of any instability in the country.

Pro-Kremlin commentators have been heard on state-run media and Telegram groups describing the coup as a pathway for Russia’s entry into Niger.

However, a Kremlin spokesperson has called for Mr Bazoum’s release and for a peaceful resolution to the crisis.

Despite the presence of some supporters of the coup waving a Russian flag and condemning France, the former colonial power, there is no evidence of any Russian involvement in the military takeover.

So we are waiting to hear what the junta leaders say about the country’s future strategic alignment – whether it maintains its ties with the West, or joins its neighbours in embracing a new Russian sphere of influence in Africa.

This latest seizure of power also raises questions about whether the slow advance of democracy seen across Africa in recent decades is now under threat.

Even as West Africa’s regional economic bloc Ecowas seeks to broker a peaceful solution, the stability of the region is more fragile than it has been for some time.

BBC