His opponents called him a social media president. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and TikTok, they insinuated, were his real political party and structure. But on election day, Peter Obi of the Labour Party stunned his doubters. He pulled over six million votes, trailing Atiku Abubakar, the presidential candidate of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP).

Mr Obi has insisted he won the election and has approached the court to upturn the victory of Bola Tinubu, the candidate of the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC).

Before the Election Day, a journalist asked Atiku about the possibility of Mr Obi’s political party winning Nigeria’s presidential election. He first smiled and shook his head to express doubt and negativity before answering the question: “They claim they have 100 million supporters online but you saw what they scored in Osun (governorship election of 2022). In fact, in the North, 90 per cent of our people are not on the internet.”

Like Atiku, many people believed Mr Obi’s political structure could not win a local government election outside Anambra State let alone a presidential poll. Their permutation was that a huge chunk of his support base existed only on the internet.

But how did “structureless” Mr Obi’s Labour Party manoeuvre the major opposition parties in many states?

Identity Politics (Religion)

The outcome of the presidential election exposed an inherent identity tension in Nigeria: an underground but intense contest between the adherents of Islam and Christianity, Nigeria’s two most popular religions.

After fighting a fierce battle to win the presidential ticket of the APC, former Governor Bola Tinubu faced another dilemma regarding who to choose as his running mate, from the north. Being a Yoruba Muslim from the South-west, he eventually chose Kashim Shettima, another Muslim (from the North) to appease the Muslim majority north.

His choice of running mate sparked a huge controversy. Many Nigerian Christians considered this as a disrespect to their religion and its large adherents in the country. They loudly and ferociously protested the Muslim-Muslim ticket and vowed to teach Mr Tinunu a bitter political lesson. Mr Obi smartly exploited the anger of the Christians , courting faithful at their places of worship.

In November 2022, the Labour Party presidential candidate campaigned at the 14th National Conference and Jubilee Celebration of the Catholic Charismatic, Delta State, violating the Electoral Act, 2022. Facing the mammoth crowd, Mr Obi appealed to the congregants for support.

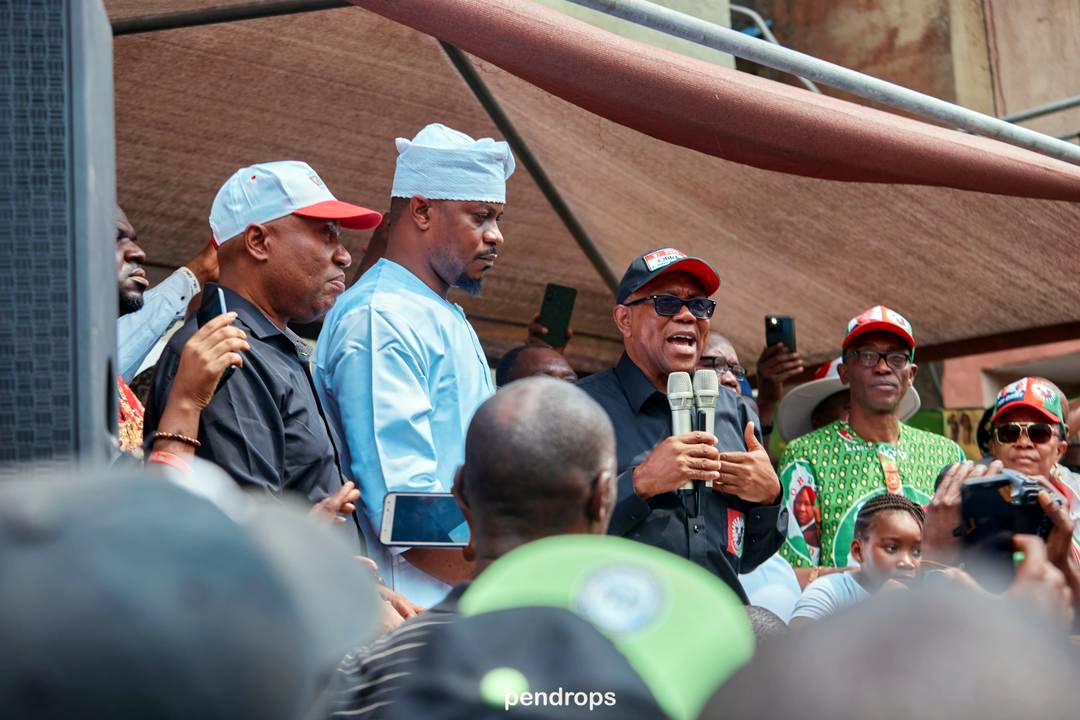

![Labour Party Presidential Candidate, Peter Obi at the Enugu campaign rally [PHOTO: TW @PeterObi]](https://media.premiumtimesng.com/wp-content/files/2023/01/FmTG-fYXECQDNxH.jpg)

“I’m asking you to vote for me because I’ll turn around Nigeria, I want to build a Nigeria where the son of nobody will become somebody, and a daughter of nobody will become somebody,” he said.

Before then, in July, he attended the Judgement Praise Night Worship with Pastor Paul Enenche and in August, he was at the Redemption Camp for the first time to celebrate the 70th Annual Convention of the Redeemed Christian Church of God, where he received a loud ovation.

“Places designated for religious worship, police stations, and public offices shall not be used for political campaigns, rallies, and processions; or to promote, propagate, or attack political parties, candidates, or their programmes, or ideologies,” Section 92(3) of the Electoral Act 2022 states.

Christian Lobby worked

Mr Obi’s consistent lobby of Christians worked for him. Many pastors openly campaigned for him and urged hundreds of thousands of their followers to ready their voter’s cards to ensure the Muslim-Muslim candidate (referring to Mr Tinubu) is humiliated on Election Day.

On the eve of the presidential election, videos of pastors sensitising their followers to vote for the Labour Party floated around social media. While there were also videos of Islamic clerics openly telling their supporters to vote for Mr Tinubu, that of Mr Obi dominated the Internet and was considered overwhelming by many observers.

Overall, while Mr Tinubu played the Muslim-Muslim card to court northern Muslims, Mr Obi projected himself as the frontline Christain in the presidential race.

As the ruling party paraded a Muslim-Muslim presidential ticket, the Nigerian Christian community felt marginalised and saw this as an invitation to a religious battle of the ballot. Mr Obi was thus their choice candidate. The outcome of the faith war clearly manifested in the results of the just-concluded election. Mr Obi won in many Christain-dominated states, including those governed by Mr Tinubu’s APC.

Ethnic Identity

Since 1999, no presidential election in Nigeria has been as ethnicised as the recent one. Nearly all the three front-runners played the ethnic card. But one of them, Peter Obi, seems to have benefitted most from it.

In June 2022, Mr Tinubu’s outburst during a campaign tour is considered a major appeal to ethnic consciousness. He said it was the turn of the Yoruba to take the mantle of leadership after President Muhammadu Buhari, a Fulani from Northern Nigeria. As a major political figure of the Yoruba stock, Mr Tinubu said it was his turn to be Nigeria’s president. He urged his kinsmen to support him to avoid a repeat of history.

Atiku Abubakar of the PDP made a similar sales pitch, saying he, as a northerner, was in the best position to address the problems facing the north.

Like Messrs Tinubu and Atiku, Mr Obi also played the ethnic card and it worked well for him.

![Atiku Abubakar, PDP presidential candidate during his campaign in Enugu [PHOTO CREDIT: Official Twitter handle of Atiku]](https://media.premiumtimesng.com/wp-content/files/2023/02/Fo85kKqWcAAfMlX-scaled.jpeg)

Since the end of the Nigerian civil war spurred by the Igbo secessionists who wanted Biafra as an independent country, the ethnic group became a victim of stereotypes from others in the country. It is common to hear unsubstantiated permutations that an Igbo president would divide the Nigerian nation.

That narrative worked against Odumegwu Ojukwu, the army officer who led the Biafra war. In 2003, he contested the presidential election against Olusegun Obasanjo and lost. Twenty years later, in 2023, many Igbos were determined to break the shackle and the stereotype that their kinsmen can’t lead Nigeria.

Enters Obi, a Successful Trader From Anambra

Why can’t an Igbo man be a Nigerian president? That was the rhetorical question many southeasterners repeatedly asked. But many socio-political analysts said that the presidency is not the birthright of any region; any individual from any region who wants it must work for it.

Mr Obi appeared to have appealed to these Igbo sentiments, as millions of Igbos across Nigeria and beyond rallied around him and campaigned for him vigorously more than they had ever done for any Nigerian president.

Before Mr Obi’s appearance on the presidential political stage, Nnamdi Kanu, the leader of the Independent People of Biafra (IPOB), a secessionist group, had resonated with many southeasterners. Though considered a minority in the South-east, Mr Kanu’s supporters described him as their saviour and the only living man who can grant them freedom from Nigeria, which some of them described as a “zoo”.

![The presidential candidate of the Labour Party (LP), Peter Obi [PHOTO CREDIT: @TheOfficialPOMA]](https://media.premiumtimesng.com/wp-content/files/2023/01/FlvH2AlWYAEXQ_d.jpg)

When Mr Obi, a successful trader from Anambra State, announced his presidential bid, many Igbos saw it as an opportunity for one of them to eventually become Nigeria’s president. The expectation was probably that Mr Obi’s election would address the imbalance in the polity and what many Igbos consider to be unfair treatment of their ethnic group.

Mr Obi’s presidential bid did not, however, stop the IPOB agitations. Armed persons suspected to be members of IPOB continued to launch attacks against politicians, electoral officials, security officials and other state institutions.

Mr Obi’s critics accused him, without evidence, of being a supporter of IPOB. Also, he refused to publicly criticise the terror group, saying his position on the different “agitations across the country” is to dialogue and negotiate.

In the long run, Mr Obi performed very well in the presidential poll, especially in the South-east. He won over 70 per cent of the votes in each of the five South-east states, securing over 90 per cent of the votes in his home Anambra State. No other candidate had such domineering support in their home state or region.

![Aerial view of the Lagos ObiDatti rally held on 1 October 2022. [PHOTO CREDIT: Instagram @levithegrapher]](https://media.premiumtimesng.com/wp-content/files/2022/10/Fd_8W_0WYAUdPyh.jpg)

Young Nigerians/Obidients

Since his return as Nigeria’s head of state in 2019, President Muhammadu Buhari’s administration has been criticised by the youth, who now seem to be more conscious about the governance, policies and politics of their country.

In 2020, a massive protest that shook the country emerged over police brutality. Some young protesters were killed in Lagos. But the government and the army denied the atrocities. The youth were stopped from protesting; they left the streets waiting for the right time to speak at the ballot box.

Before and after then, bad news never ceased to appear as headlines of major Nigerian newspapers. Killings and kidnappings for ransom became a booming business in the North-west; Terrorism resurfaced in the North-east; ritual killings turned incessant in the South-west; IPOB continued its criminal acts in the South-east; farmer-herder violence did not stop; internet fraudsters became the stars of the streets and so on.

![Peter Obi speaking at a gathering of Young people in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State [PHOTO: Channels TV]](https://media.premiumtimesng.com/wp-content/files/2023/03/peter-obi-uyo-2.jpg)

The widespread insecurity, the skyrocketing cost of living made Nigeria a hell for citizens. Many brilliant folks would prefer to leave the country for good — they called it “japa”. Many were tired and needed a messiah to retire the old order seeking presidential power. They needed someone without much corruption baggage to his credit.

The angry youth sought to rally around a Nigerian politician to break what appears like a generational curse on the country. Mr Obi was their man for the job. They wanted a thunderstorm that would strike the old folks of Nigerian politics out of power. Mr Obi appeared in the horizon and they embraced him without much vetting. Neglecting the corruption allegations he faced, they promoted him to sainthood with their savvy use of social media.

Seizing the Historical Moments

By weaponising the anger and yearning of the youth, Mr Obi appeared to be adhering to the law of generational myopia. Also known as Gregory, Mr Obi, 61, appears to know how to play the politics of popular demand. In the Laws of Human Nature, Robert Greene teaches how to smartly take advantage of the masses’ emotions and a generational movement for change to attain power.

“Knowing in-depth the spirit of your generation and the times you live in, you’ll be better able to exploit the zeitgeist,” Greene says. “You will be the one to anticipate and set the trends that your generation hungers for.”

The strong-willed, energetic young Nigerians on social media, who fondly call themselves “the cocoa-nut head generation”, started the revolution of retiring alleged corrupt politicians who have ruled since Nigeria returned to democracy in 1999. Most of them were participants in the nationwide EndSARS protests, leading to the disbandment of a notorious police unit in 2020.

They would not leave the streets even after authorities disbanded the SARS, the police unit that so much disgusted them with brutality and extra-judicial killings. They would further trend “EndBadGovernment”. The protest ended in blood and tears after menacing soldiers fired fusillades of bullets to disperse demonstrators.

Many of them returned to agitation online as election season drew closer. They had been accused of being social media voters and they wanted to break the stereotype. They formed the support base for Mr Obi, a man they considered to be less corrupt and a lesser evil.

Are you still wondering how he got over six million votes during the just concluded presidential election?

Mr Obi seized the historical moments of hunger for change and retirement of old, corrupt politicians by Nigerian youth; the fear of another eight years of marginalisation of the Igbos and their apologists and the battleline of ballots drawn between the Christians and Muslims. While many mocked Mr Obi for having no structures, the above-mentioned demographicsvformed a strong political base for him.

They called themselves the Obidents.

PREMIUM TIMES