(CNN) Amid the phenomenal response to Amanda Gorman, who delivered a poem to wide acclaim at President Joe Biden’s inauguration, lurked a bleaker current: responses that summoned for me the story of enslaved early American poet Phillis Wheatley.

In 1773, Wheatley became not just one of the first Black women but one of the first American women to be published when her book of poems, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,” was printed in London.

Wheatley traveled to England with her master’s son when her book was published, and according to biographer Vincent Carretta, probably returned to America only on the condition she be granted her freedom.

“Wheatley was a genius by any standard. Brought to America from Africa in 1761, at 7 years old, she was educated by her enslavers who had lost a daughter her age. Wheatley learned English and Latin and wrote her first poem four years later.

So remarkable was the story of the young slave poet that a bevy of Boston worthies, including John Hancock, examined her and testified to the authenticity of her poems to confirm what many surely doubted — that a young enslaved Black girl could produce such polished work. But along with praise came unabashed, racist criticism.

The West Indian slaveholder Richard Nisbet dismissed her “silly poems.” Thomas Jefferson, who speculated on black intellectual inferiority in “Notes on the State of Virginia” (1785) wrote, “Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately [sic]; but it could not produce a poet. The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism.”

Here Jefferson simultaneously acknowledged Wheatley’s poetry while condescendingly dismissing them, much like Gorman’s modern critics. Just in case, he also slyly questioned her authorship for all those who held up Wheatley’s poetry as proof of Black equality. For a long time, American literary critics cast such judgment on Wheatley’s poems.

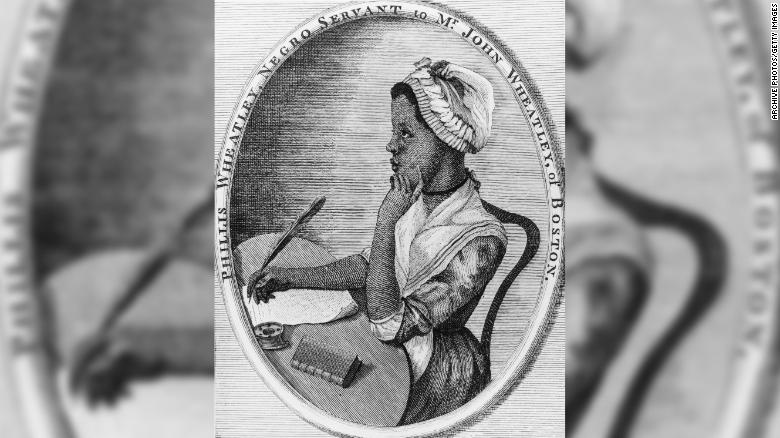

Engraved portrait of Phillis Wheatley at a writing desk, circa 1780.

Engraved portrait of Phillis Wheatley at a writing desk, circa 1780.

Recently, a writer for the conservative British magazine, The Spectator, criticized Gorman in language that echoed these dismissals of Wheatley’s talent. After condescendingly complimenting Gorman on her appearance and performance at the Inauguration (and before comparing her diction and delivery unfavorably to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s), journalist Melanie McDonagh called the “The Hill We Climb” a “terrible poem.”

Line by line, as she questions the poem’s grammar, syntax and style, she ironically punctuates her criticism with such verbal treasures as “Eh?” and “Dunno.” Clearly conversant in the colonial Lord Alfred Tennyson’s school of poetry, McDonagh concludes, “The Hill We Climb turns out, I think, to be just a bit rubbish.”

I “dunno” but I think she missed an “of” before rubbish in that sentence. African American women have long been at the receiving end of such half-baked and belittling put-downs.

McDonagh’s dismissal was staggeringly patronizing in its picking apart of Gorman’s structure, grammar and use of poetic devices: “I got the sentiment, I got the stream of consciousness, the emotion, I got the sub-Martin Luther King flow. But trying to make the whole thing cohere, structurally and grammatically — and in terms of sense — was another matter.”

Another critic, Malcolm Salovaara of The American Conservative, went even further, calling Gorman’s poem and performance propaganda and “nothing less than an embarrassment to our country.” Such criticisms are reminiscent of the kind Wheatley was subjected to and more recently, takedowns of other Black women poets blocked from the mainstream literary canon, too numerous to list.

One recent criticism that stands out came from the National Review, when Tim Cavanaugh offered cold praise for the Inauguration Day poem of one Black woman, Maya Angelou (who had recently died) by saying he didn’t really like her work, but that it was comparable to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (notably a classic by a White male Romantic poet) when put alongside the inaugural poems of Richard Blanco, a gay Latino man, and Elizabeth Alexander, a Black woman whose work he described as “a poem so boring economists now believe it reduced America’s 2009 GDP by a quarter of a percentage point.”

Neither McDonagh’s or Salovaara’s reactions, though, have been the rule. Far from it. Gorman’s poem has been generally received with fulsome praise and accolades. Her book of poems sold out on Amazon, she will read a poem at the Super Bowl and she has received a modeling contract. And yet even this praise, in some of its forms, feels like history repeating itself in racist terms.

She has been touted by nearly all commentators as truly exceptional — yet treated by others with the kind of racial exoticism that is too often the subtext of people’s reactions to Black excellence and talent. Some of us continue to fawn over successful African Americans, while remaining blind to the plight of a majority of Black people, who face wealth inequity, health disparities and are at higher risk of experiencing police brutality.

Though separated by centuries, wildly disparate life experiences and so many other differences, this echo between Wheatley and Gorman serves as a reminder: Black women poets, from Wheatley to Gorman, seem to have an impossible task balancing their mastery of art with the authenticity of their experiences and history.

Despite her classical style of poetry and deeply felt Christian universalism, Wheatley proudly asserted her African identity, signing her poems “Ethiop” and naming Terence, the African poet from antiquity, as her inspiration.

Like Gorman, she found herself internationally feted. The French philosopher Voltaire, British abolitionists Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson, and American revolutionaries such as Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rush praised her poems.

An admiring John Paul Jones, the daring patriot naval commander, sent his verses to her. When Wheatley wrote to George Washington, enclosing a poem she had written in his honor, he replied with a desire to meet “one so favord by the Muses.”

Despite naysayers, both Wheatley and Gorman elicited broad admiration, especially from women.

In Massachusetts, Jane Dunlap cited “the young Afric damsel” as an inspiration for her own poetry, just as scores of poets across the world were moved by Gorman.

And just as Wheatley’s poetry has long outlived criticism, no amount of sour grapes can mar Gorman’s glorious and enduring achievement. Or the moment when the first Black and Indian American woman became the Vice President of the United States, or when a pastor from the historic Black abolitionist denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, delivered the inauguration’s final benediction.

Somewhere Wheatley’s spirit surely approved of Gorman’s poem and the proceedings. For the millions of viewers who tuned in to watch the inauguration of President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, one of the most uplifting parts of the ceremony was without a doubt Gorman’s ode to American democracy.

In “The Hill We Climb,” she beautifully captured the unending yet hopeful black struggle to realize its promise. Commentators compared her to famous African American women poets, who preceded Gorman on the Presidential Inauguration stage.

The late Maya Angelou at President Bill Clinton’s 1992 inauguration and Elizabeth Alexander at President Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2008. But the real predecessor of the nation’s first young poet laureate, is the foremother of American poetry, the enslaved teenaged girl from 18th century Massachusetts, Phillis Wheatley.Get our free weekly newsletter

Gorman shares Wheatley’s clear-eyed view of the trials that Black people faced in the slaveholding republic. Wheatley’s poems do not shy away from the dark history of enslavement while committing to a vision of American democracy that may encompass all. Compare Wheatley’s unpublished poem with Gorman’s meditation on democracy.

Wheatley wrote:But how, presumptuous shall we hope to find

Divine acceptance with th’ Almighty mind—

While yet (O deed ungenerous!) they disgrace

And hold in bondage Afric’s blameless race?

Both young poets point to the acute danger racism poses to the American experiment in republican government.

At a moment when an unregenerate racist minority would destroy that experiment rather than accept equal Black citizenship, their words remain a clarion call to recommit ourselves to preserve America’s interracial democracy.